Dear reader… your burdened author has several posts sitting in the drafts box. The author has wanted to tackle some of the more interesting things around photographic “exposure”, or more specifically pictorial “exposure” for a good deal of time. Sadly, because the author’s maligned and misinformed worldview is so utterly deformed and distorted away from much of the orthodoxy of publications and beliefs around “colour” currently out in the wild, they’ve found themselves at an impasse; Should the author jump right in, or in the interest of “pedagogy”, try to build a case for framing the problem surface from the author’s particular bent worldview? The author sees no other way forward other than to choose the latter.

In order to tackle the deconstruction and exploration of the ideas in the prior questions, as well as new questions around “contrast”, “exposure”, and whatever other cognitive mechanisms craft folk have employed, it is key to get one critical, albeit false, belief out of the way. Then, once leaning hard into this absolutely foundational idea, we can move forward to dismantling some other ideas. These other ideas are, by way of being such common vernacular that they should be considered “obvious”, will hopefully leave us all the more perplexed in terms of our definitions.

This post is sort of the “official” post of another side post in the first instalment of Questions to the Editor: What the F*ck is a Picture? post. Hopefully this post will wrap some of the ideas in that Q&A post up into a more directed warhead that we can build on.

Question #34: Is there an almost implicit and false assumption in virtually all orthodox ideas around pictorial depiction, that becomes amplified within the realm of photography?

Historical Narratives, as Legitimizing Force

If we crawl around online and read any number of forum posts, general discussion points, or even “research” papers, there is a fascinating pattern.

“The render is so realistic!”

“VR is going to get better and no one will know that it’s not reality!”

“How can I get realistic colours in my photograph?”

In these sorts of common statements, there is a pernicious problem that rests at the foundation of a colossal number of subsequent erroneous assumptions when discussing “what we see” within a pictorial depiction. Did you spot it? It is arguably about as seductive of a myth as they come, so we should be forgiven for missing it.

Let’s get some foundational bits in order before we try to tackle this. For starters, hopefully you’ve arrived here at Question #34 with at least a reasonable understanding that stimuli is not colour. In fact, we are going to abandon the “duality” of the use of “colour”, and instead separate the ideas into these two more clearly framed domains.

- Stimuli. The energy at the first touchpoint of our sensory systems.

- Colour. The cognitive culmination of the meatware computations.

We should purposefully leave these as fuzzy points, because each of these ideas cascades down into significantly more slippery language boundaries that virtually no one on the planet has a very good handle on. For example, the influential psychologist James J. Gibson wrote an entire paper on the subject of demarcation points around stimuli1.

The moral of my argument is that a systematic search for relevant stimuli, molar stimuli, potential stimuli, invariant stimuli, specifying stimuli, and informative stimuli will yield experiments with positive results. Perhaps the reservoir of stimuli that I have pictured is full of elegant independent variables, their simplicity obscured by physical complexity, only waiting to be discovered.

If the experience of Gibson was open to the ontological partitioning of “stimuli” being potentially obscured by complexity, most folks should at least be cautious in their own assertions. This is an order of a magnitude more true for your inept author.

The key point is that this post hinges on a broad separation between, loosely, the energy “outside” of us as mediated by our sensory organs, and the conscious experience of what it is we have inferred from the energy “arrangement”.

Picture Stimuli

When we consider a pictorial depiction, our first point of query might be to ask ourselves what a useful demarcation of “the picture” is. For this exercise, we are going to consider the use case that most of the folks reading are familiar with, although our definition can easily be relaxed to other ideas. Let’s lay out a demarcation of pictorial depiction such that we can discuss components. To begin:

Picture Stimuli

A two dimensional presentation of stimuli, at a given viewing distance to an audience.

Our picture must only be considered relative to the stimuli presented to our audience. There is no other metaphysical information beyond the memory priors and broader cognition of the audience member. We could extend this slightly to suggest that unintentional or intentional stimuli, such as auditory2, or even olfactory3 stimuli, will have an influencing context upon our cognition. For our purposes, we need to demarcate “the picture”, and this definition is sufficient at this stage. To be clear, there is no secret signal of “scene” or “display” or any of that mumbo jumbo. There is only the audience, and the intentionally presented stimuli.

So given we have a definition of some sort of a pictorial presentation state, and that we must only consider the as presented stimuli, we can see that this is an impoverished lens. While we have described a scientism based framing of “a picture”, we’ve grossly failed to describe the purpose of a picture. More clearly, what is it that the presented picture is doing, or intended to achieve, within the meatware cognition of the intended audience?

Pictorial Depiction

Let’s turn to Etymology Online for the definition of “picture” as a working starting point:

early 15c., pictur, pictoure, pittour, pectur, “the process or art of drawing or painting,” a sense now obsolete; also “a visual or graphic representation of a person, scene, object, etc.,” from Latin pictura “painting,” from pictus, past participle of pingere “to make pictures, to paint, to embroider,” (see paint (v.)).

While it is almost too obvious to state, we are going to borrow that bolded text as our definition of pictorial depiction, if only as a communal entry point goal at first. We take it for granted, but hopefully we will see that this a priori assumption is something that requires deeper scrutiny. If we accept this statement, the question we should be asking ourselves is how this “representation” emerges in the meatware celery powered organism.

Pictorial Depiction

A visual or graphic representation of a person, scene, object, etc.

The Apelles “Test”, as Recounted by Pliny the Elder

There is a piece of lore recounted by Pliny the Elder as recounted in his Natural History, Chapter 36, Artists Who Painted with the Pencil. The story recounts the work of Apelles, a name that will make a reappearance if your dreadful author manages to push out another log into this fire.

Apelles, for those who are unaware, was a significant artist at the time. He was the court artist for none other than Alexander the Great. But the part of this tale that intrigues us is one of the piece of lore around his painting of horses. Here is Pliny the Elder’s recounting of the tale:

There exists too, or did exist, a Horse that was painted by him for a pictorial contest; as to the merits of which, Apelles appealed from the judgment of his fellow-men to that of the dumb quadrupeds. For, finding that by their intrigues his rivals were likely to get the better of him, he had some horses brought, and the picture of each artist successively shown to them. Accordingly, it was only at the sight of the horse painted by Apelles that they began to neigh; a thing that has always been the case since, whenever this test of his artistic skill has been employed.

That’s right dear reader, Pliny the Elder would have us believe that Apelles was able to create a “simulacrum” of “reality” upon the canvas so veridical to “reality” such that horses neighed! Now of course we might be a tad skeptical believing these legendary tales hold a degree of veracity, but we can at least catch a glimpse of a thematic regarding picture looking, even if our protagonist happens to be a quadruped that neighs. Was Pliny the Elder mythologizing? Was Apelles engaging in a carefully crafted bit of showmanship magic to promote his abilities? We will never know for certain. Regardless, the theme here is that a picture is a magical “substitute” for this thing we label as “reality”.

In the modern era, our understanding of picture looking is fraught with these sorts of assumptions. Why should an ideal picture aspire to embody anything but a perfectly idealized replication of the stimuli presented to the artist’s position in time and space? This is such a seductive idea that there seems to be a collective assumption of truthfulness of the idea, without even a shred of interrogation of the credibility of the idea.

Thankfully dear reader, we are not of that sort of reasonable mind to take perfectly logical assumptions for granted. For the delusional who are reading this nonsense, we expect a higher degree of rigorous investigations to fuel our madness…

Picture Reading (?)

For our purposes, we are first going to draw attention to a more fundamental question; whether or not pictorial “understanding” is immediate and “innate”, or if there is some component of a learned, and therefore cognitively derived, interaction required. A visual “literacy” equivalent to a literary reading of texts, when faced with articulations of picture stimuli.

Segall notes in The Influence of Culture on Visual Perception4 that while somewhat infrequent, some anthropologists were able to present pictorial depictions to their studied indigenous cultures, who often times were not familiar with pictorial depictions:

Until the last few decades, most anthropologists had the opportunity of being the first to show a photograph of local scenes to members of the group they were studying. While anecdotes on this point have not been systematically reported or collected, reputedly the common finding was a temporary failure of perception that surprised the anthropologist unless he had been primed for this failure through hearing the reports of other anthropologists.

Segall goes on to quote a passage from Herskovits. Warning, the following passage has the stink of imperialism, colonialism, and racism. It is hoped however, that folks will be able to understand the point communicated:

I have had an experience of this kind, similar to that reported from many parts of the world by those who have had occasion to show photographs to persons who had never seen a photograph before. To those of us accustomed to the idiom of the realism of the photographic lens, the degree of conventionalization that inheres in even the clearest, most accurate photograph, is something of a shock. For, in truth, even the clearest photograph is a convention; a translation of a three dimensional subject into two dimensions, with color transmuted into shades of black and white. In the instance to which I refer, a Bush Negro woman turned a photograph of her own son this way and that, in attempting to make sense out of the shadings of greys on the piece of paper she held. It was only when the details of the photograph were pointed out to her that she was able to perceive the subject [Herskovits, 1959a, p. 56; see also Herskovits, 1948, p. 381].

Deregowski, writing in Real Space and Represented Space: Cross-Cultural Perspectives5, notes other evidence of a lack of immediacy or innate comprehension:

There are, however, some contrary and puzzling and not easily dismissible findings, as in Landor’s (1883) report of his life among the Ainu of northern Japan. His Ainu companions who saw him draw a picture could not say what it represented. More recent observations by such distinguished and experienced researchers as Doob (1961), Cole and Scribner (1974), and Barley (1986) show similar difficulties. The Fulani of Nigeria, among whom Doob worked, had on occasion labelled a distinct picture of an aeroplane a fish. Cole and his coworkers presented the Kpelle with very clear photographs (two are reproduced in Cole and Scribner’s [1974] book) and some of these subjects misperceived them. Dowayos, to whom Barley (1986) showed postcards of animals for identification, could not identify them. The balance of the evidence is therefore that, although it occurs infrequently, clear pictures are misperceived, or, to be more precise, pictures that are perceived in some cultures are not perceived in others.

In the same work, Deregowski cites a piece by A. B. Lloyd:

There are also reports showing that reducing the influence of the nonpictorial cues greatly enhances perception by the pictorially unsophisticated, sometimes with rather dramatic consequences, as in the case of a slide show in Uganda reported by Lloyd (1904) early in the present century. The event was described thus:

When all the people were quietly seated, the first picture flashed on the sheet was that of an elephant. The wildest excitement immediately prevailed, many of the people jumping up and shouting, fearing the beast must be alive, while those nearest to the sheet sprang up and fled. The chief himself crept stealthily forward and peeped behind the sheet to see if the animal had a body, and when he discovered that the animal’s body was only the thickness of the sheet, a great roar broke the stillness of the night.

And from another passage from Colin Wilson, recounting6 Thomas Edward Lawrence’s recounting his revisiting to the Middle East after writing Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the book that would go on to become the basis of Lawrence of Arabia:

Another example might make clearer what I mean by ‘Visionary faculty’. T. E. Lawrence tells that when he showed the Arabs the portraits of themselves that Kennington painted for The Seven Pillars, most of them completely failed to recognize that they were pictures of men; they stared at them, turned them upside-down and sideways, and finally hazarded a guess that one of them represented a camel, because the line of the jaw was shaped like a hump! This seems incomprehensible to us because we have been looking at pictures all our lives. But we must remember that a picture is actually an abstraction of lines and colours, and that it must require a certain mental effort to interpret those lines and colours as a man or a sunset. We make the effort unconsciously, and so are not aware of it.

The research into pictorial depictions and the efficacy of comprehension carries on even to today. Bovet and Vauclair in their 1999 paper7 note more evidence on the lack of immediacy of comprehension:

In summary, cross-cultural studies have demonstrated that adults who have never seen any two-dimensional representations may experience difficulties recognising pictures; these participants need some explanation and some experience with a photograph (or a drawing) before being able to perceive what it represents.

So why the need for this accumulation of historical observations around picture “seeing”? What does this have to do with our discussions here, in a website dedicated to “digital colour” and such artistic artifacts such as photography? Given the significant role of motion pictures in the cultural zeitgeist, Lloyd’s passage referenced in the Deregowski work is significant. It broadly attaches some sense of an intentioned conflation between a pictorial depiction and a veridical experience of “reality”. All wrapped nicely with an attempt to suggest that the pictorial depiction was so compelling that it induced “surprise” and “shock”. If this smacks of spectacle, it is likely no accident…

Into the Moving Picture Era

Anyone familiar with the history of the moving picture in the Eurowestern mind may have come across a familiar piece of lore. Specifically, Lumière’s Arrival of a Train (L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat). The following passage is from Martin Loiperdinger, a professor of media studies, discussing one of cinema’s founding myths8:

Even the German Railway’s customer magazine picks up the gag, visually embellishing the supposedly panicky reaction: “The spectators ran out of the hall in terror because the locomotive headed right for them. They feared that it could plunge off the screen and onto them.” The Munich Abendzeitung purportedly knew that “at the time, people, appalled by Arrival of the Train, were said to have leaped from their chairs.”

Not only does Loiperdinger provide evidence in support of the belief that the “panic” the audience experienced may have been mythologized, but we can see a striking similarity to Lloyd’s passage above. We should at least have our spider sense tingling.

Is it at least possible that the peculiar faith in the effectiveness of the picture to evoke a veridical response as “real experience” was re-employed to fuel the promotion of Lumière’s work? Or, are the numerous accounts from anthropologists and researchers of pictorial depictions failure to induce communication false? Is there something else going on here? Loiperdi arrives at a conclusion that refutes the founding cinematic myth:

First, no one has yet proven the existence of a panic among the audience for the cinematographic locomotive pulling into the station of La Ciotat. Persistently reiterating this panic legend, film history has ascribed a founding myth to the medium that categorically assigns the power to manipulate spectators to the film on screen.

Second, the retrospective assessment of L’arrivée du train à La Ciotat as a precursor of direct cinema is completely misbegotten. The belated enthusiasm for the realism of “randomness” is derived from the visual surface of the film. It ignores the fact that Louis Lumière staged the profilmic event, something that direct cinema’s conception of documentary film strictly rejects.

If we accept Loiperdinger’s work, we have been presented with the possibility that the audience was not fooled into “experiencing” the train coming at them as though they were “standing there”. This connection between the mythologized legendary narrative and the likely more historically grounded version researched by Loiperdinger, should give us pause in our assumption that a picture is an illusory simulation of the event in front of the camera. Of course, in our contemporary era, we might draw attention to the more obvious points such as the lack of “at camera” audio, or colour, or other stimuli, to question the narrative myth. Yet the myth of this cinematic moment is propagated today, and worse, so too is the deeper idea of “reality” of the pictorial depiction.

What does seem intriguing here is that the reports on the abilities of primates and other creatures varies on their ability to comprehend pictorial depictions. On the one hand, there is a large body of work showing complications with picture reading, while on the other it seems some that accept, without the need for significant evidence, that pictures are capable of magically inducing “reality”.

At this point, we shall frame this meta “picture duality” as:

- The picture as an encoded “surface”, such as an RGB encoding of wattages.

- The picture surface as encoding a depiction.

Dual Modes of Seeing

The central idea of depiction is intriguing, given we, as meatware organisms, well versed in the activity of parsing stimuli like tea leaves, often are only consciously aware of the endpoint of the computations. We seem prone to immediately jump to the interpretation of the stimuli, as opposed to paying attention to the canvas and the arrangement of the stimuli.

Seeing As

Wittgenstein suggested a notion of “seeing as meaning”. Seligman9 notes:

Wittgenstein refers to these experiences sometimes as seeing-as, sometimes as seeing an aspect or noticing an aspect. By this he means to describe cases in which we might say, looking at a line drawing, “I see a face,” or “I see this as the face of my friend so-and-so.”

When we are discussing digital colour pictures, this “seeing-as” is the result; the audience has already reasoned through the stimuli, and specifically, if we follow the patterns outlined in Question #29, Question #30, Question #31, Question #32, and Question #33, inferred a meaning that is computed from the differential gradient domain relationships of neurophysiological signals10111213. The audience has behaved as Sherlock Holmes, sought out and pieced the clues of the case together, and focused upon the conclusion.

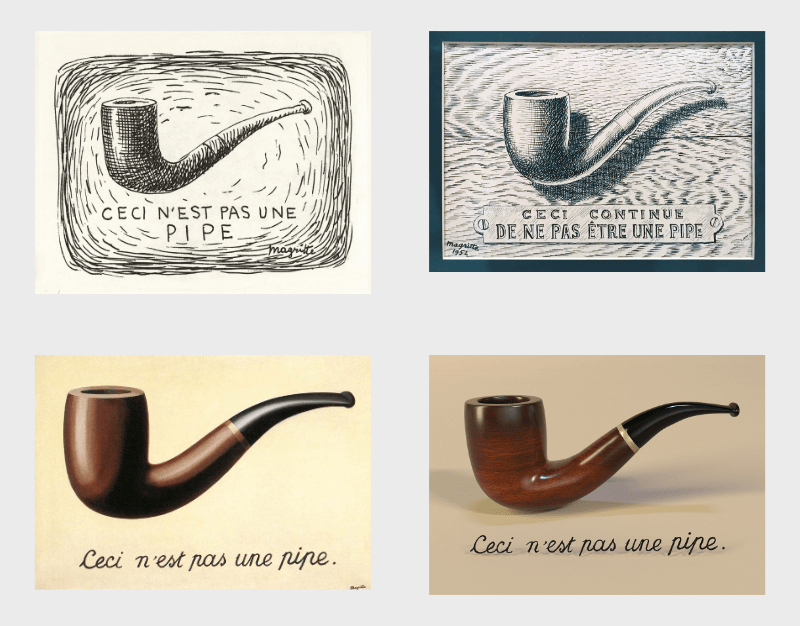

Seeing In

A more refined variation of Wittgenstein’s “seeing as” was introduced by Wollheim in Art and its Objects14. Wollheim expanded upon “seeing as”, and introduced the idea of “seeing in”. Image authors are likely familiar with the learned experience required to evaluate the pictorial depiction on the “picture as surface” level, where the analysis is at the craft level. If you’ve ever uttered “Phew does this adjustment I made to the picture ever look like sh*t!” you’ve engaged in this seasoned and experienced lens of judgement. Of course the demarcation between “Seeing As” and “Seeing In” is muddier than the turbid waters in an arena toilet, but it is useful for us to try and distinguish between the two formulations.

Wollheim states:

What is distinctive of seeing-in, and thus of my theory of representation, is the phenomenology of the experiences in which it manifests itself. Looking at a suitably marked surface, we are visually aware at once of the marked surface and of something in front of or behind something else. I call this feature of the phenomenology “twofoldness.” Originally concerned to define my position in opposition to Gombrich’s account, which postulates two alternating perceptions, Now canvas, Now nature, conceived of on the misleading analogy of Now duck, Now rabbit, I identified twofoldness with two simultaneous perceptions: one of the pictorial surface, the other of what it represents.

Here, Wollheim draws attention to our ability to simultaneously be aware of the marks in a pictorial depiction surface, and our ability to read the marks within the greater collection of other marks. When the constellation of the encoded marks aligns with a sufficient decoding by an audience, meaning is created.

Wollheim encourages us to lens the reading of a pictorial depiction of “Seeing X in Y”. We can see a “duck” in the picture marks. We can see a rabbit in the picture marks. Wollheim affords us a clearer separation between the picture as a surface, and the picture surface as a vessel of meaning encoded in marks.

To bundle all of these seemingly disparate ideas into a one bag of clams for this Episode One, we’ve focused on what we could consider The Realist Myth; the belief that a photograph, or more broadly any picture, “reproduces” the “reality”.

Answer #34: The first portion of the answer to the founding myth is the idea that there is an immediate and “innate” reality present in a photograph or picture. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that a picture is no more innately understood than any other written text, making claims of “reality” a fictional construct.

As it turns out, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that we must parse and interpret the abstract idea of marks present in a pictorial depiction. This is probably an underwhelming building block for our dear readership. This subject will hopefully be elucidated in the next posts. It was felt that cramming more into this portion would have yielded something even more of an abomination than what is currently presented.

If we leap forward, we might ask ourselves what an idealized “form” of the picture might be. That is, what is an “idealized” picture if the meaning is not present in front of the camera or painter? This will very elegantly dovetail into our next myth, which we explore now that we have hopefully dismissed some sort of magic reality.

Onward, to Episode Two…

- Gibson JJ. The concept of the stimulus in psychology. American Psychologist. 1960;15(11):694-703. doi:10.1037/h0047037 ↩︎

- Vroomen J, Gelder BD. Sound enhances visual perception: Cross-modal effects of auditory organization on vision. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2000;26(5):1583-1590. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.26.5.1583 ↩︎

- Tsushima Y, Nishino Y, Ando H. Olfactory Stimulation Modulates Visual Perception Without Training. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:642584. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.642584 ↩︎

- Segall MH, Campbell DT (Donald T, Herskovits MJ (Melville J. The Influence of Culture on Visual Perception. 1st ed. Bobbs-Merrill Co; 1966. ↩︎

- Deregowski JB. Real Space and Represented Space: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Behav Brain Sci. 1989;12(1):51-74. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00024286 ↩︎

- Wilson C. The Outsider. Dell Pub. Co.; 1956. ↩︎

- Bovet D, Vauclair J. Picture recognition in animals and humans. Behavioural Brain Research. 2000;109(2):143-165. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00146-7 ↩︎

- Loiperdinger M, Elzer B. Lumiere’s Arrival of the Train: Cinema’s Founding Myth. The Moving Image. 2004;4(1):89-118. doi:10.1353/mov.2004.0014 ↩︎

- Seligman DB. Wittgenstein on Seeing Aspects and Experiencing Meanings. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 1976;37(2):205. doi:10.2307/2107192 ↩︎

- Now we should obviously make it clear that when we are talking about how a meatbundle reads the gradient domain relationships of stimuli, there is a tremendous window here for cultural, sociological, and other such prior experiences. We can catch glimpses of this based on how folks think about time in relation to their priors of written language directionality5, or how cultures with unique pictorial frequency experience pictorial depiction correspondence6, or even how memory influence the cognition and categorization of colour7. We need to allocate a significant window for a plasticity of colour cognition when it comes to cross cultural ideas. ↩︎

- Boroditsky L. Does Language Shape Thought?: Mandarin and English Speakers’ Conceptions of Time. Cognitive Psychology. 2001;43(1):1-22. doi:10.1006/cogp.2001.0748 ↩︎

- Deregowski JB. Real space and represented space: Cross-cultural perspectives. Behav Brain Sci. 1989;12(1):51-74. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00024286 ↩︎

- Pérez-Carpinell J, Pérez-Carpinell J, De Fez MD, Baldoví R, Soriano JC. Familiar objects and memory color. Color Res Appl. 1998;23(6):416-427. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6378(199812)23:6<416::AID-COL10>3.0.CO;2-N ↩︎

- Wollheim R. Art and Its Objects. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2015. ↩︎

2 replies on “Question #34: What the F*ck is Photography’s Founding Myth (And Why the F*ck Should We Care)? Episode One”

I always have thought that when people refer to something as “realistic”, they describe something that stimulates them similarly to how “real life” stimulates them.

So the most “realistic” depiction of something would be the one that manages to compress the cognitive experience caused by “real life” onto the medium with the minimal loss.

I will have to wait until your next post to get my mind blown further 😀

LikeLike

I too believe that “realistic” is a placeholder for something that might be more reasonably described as “familiar mechanisms”.

Having crawled over this surface for too long, I believe that our picture reading leans in *incredibly* hard to existing reading priors. These priors may not be mere memory priors, but also possibly biological.

That is all to say why this post was a requirement as a dependency, for it is impossible to make a case for a particular version of picture reading before being aware that we are indeed parsing the stimuli within cognition.

LikeLike