We’ve been talking about “pixels” in terms of little squares that can emit light. I’d like to point out that Alvy Ray Smith, one of the key explorers of the alpha channel, has had a rather solid push back about leaning on the concept of “little squares” geometry exclusively. Mr. Blinn, who we introduced previously, also has written a wonderful exploration of the meaning of a pixel.

Loosely, there are a number of ways to interpret what a pixel is. For our purposes, as mere mortals and not members of the pantheon of imaging deities, we are going to carry on focusing on the idea of discrete little squares, or sampled geometry and light1. Sorry Mr. Blinn and Mr. Smith, it’s probably too much too soon to depart from discrete samples just yet…

Question #23: How do we move an emitting pixel over another emitting pixel?

Let’s pick up from the movement of the red pixel in Question #22 , and rewind just a bit, back to theoretical red pixel tuned to 50% emission…

In our example, we suggested that our pixel had moved down slightly, straddling the lower pixel window that was turned off…

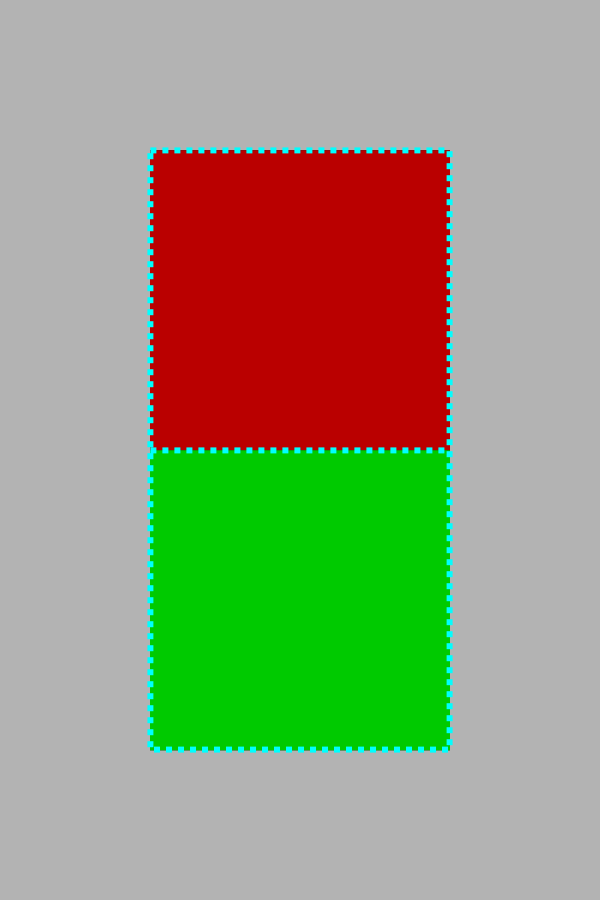

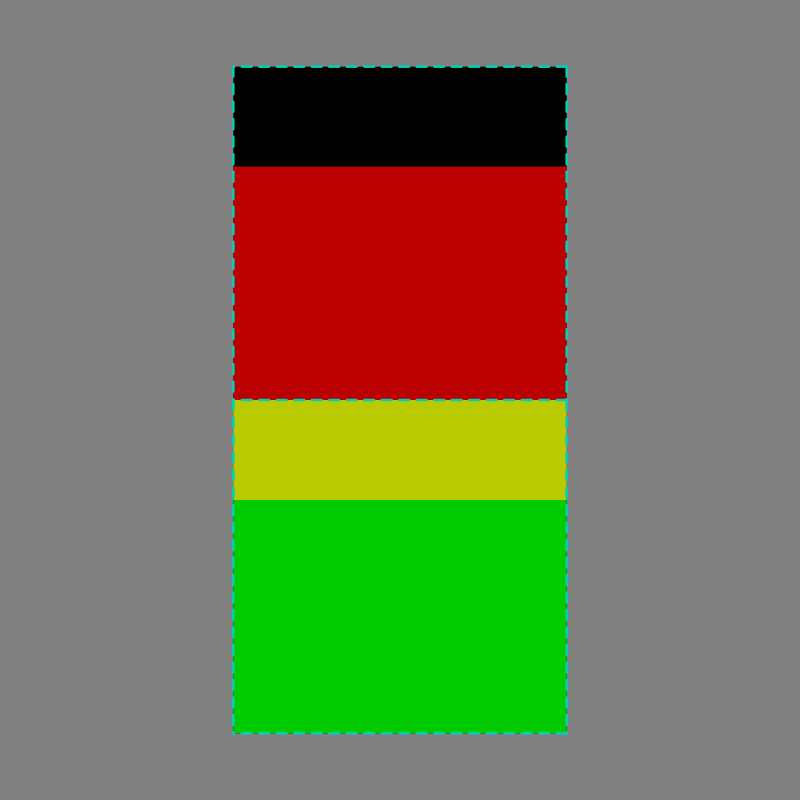

And now for a twist! What if, instead of moving over a pixel window with no emission, that the pixel it was moving into were “on” to some level of emission? So rewind and place the two pixels one over the other…

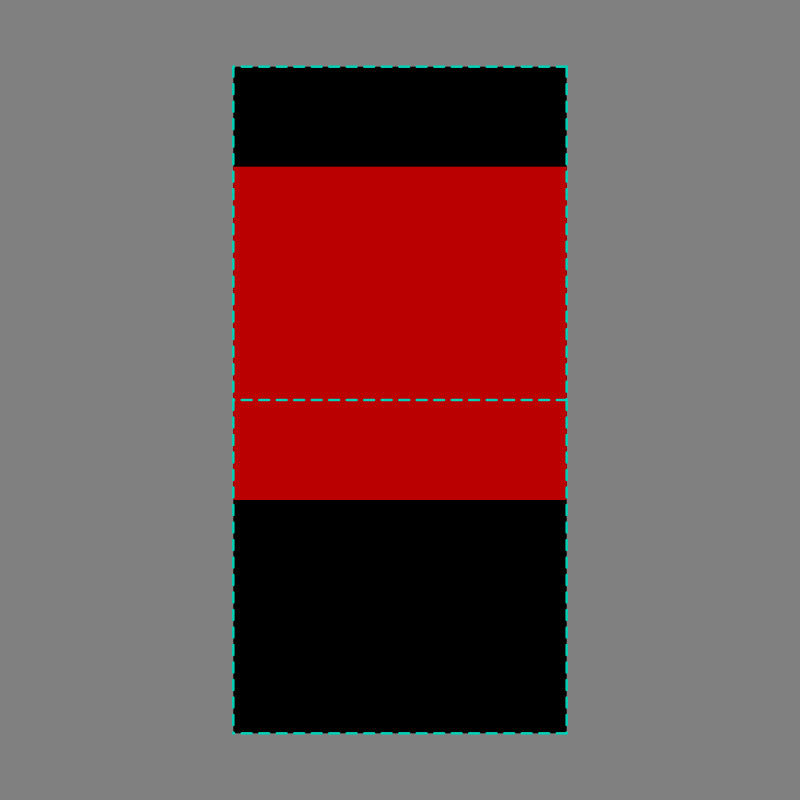

Now let’s take the exact same movement of the red pixel from Question #22. Let’s see what the result would be…

Here, our red emission of 50% has been mixed with our green emission of 60%. The result? That yellow looking band. What’s happened here? The three channels have been added together, which is exactly what we’d expect with a reddish and greenish light!

GREEN_PIXEL_EMISSION[0%, 60%, 0%] + RED_PIXEL_EMISSION[50%, 0%, 0%] = RED_AND_GREEN_PIXEL_EMISSIONS[50%, 60%, 0%]

As you know, when we mix red and green light, we get a yellowy mixture of the wavelengths from the sRGB diodes.

We know that we are not finished, of course, as we have not encoded the linear light emissions for our output display device yet. To do so, if you recall back to Question #22, we need to consider both the geometry of the pixel windows and the emission of the pixel we moved to get the overall quantity of light. If this is a slippery idea, refresh by going back to Question #20 and covering the core fundamentals of the idea of geometry and it’s relationship with quantities of light.

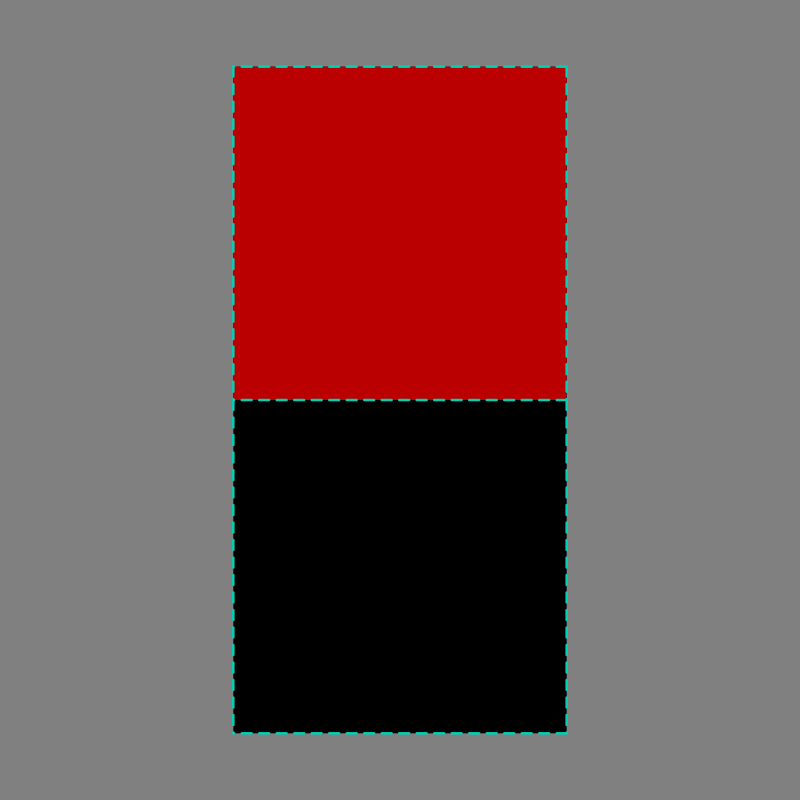

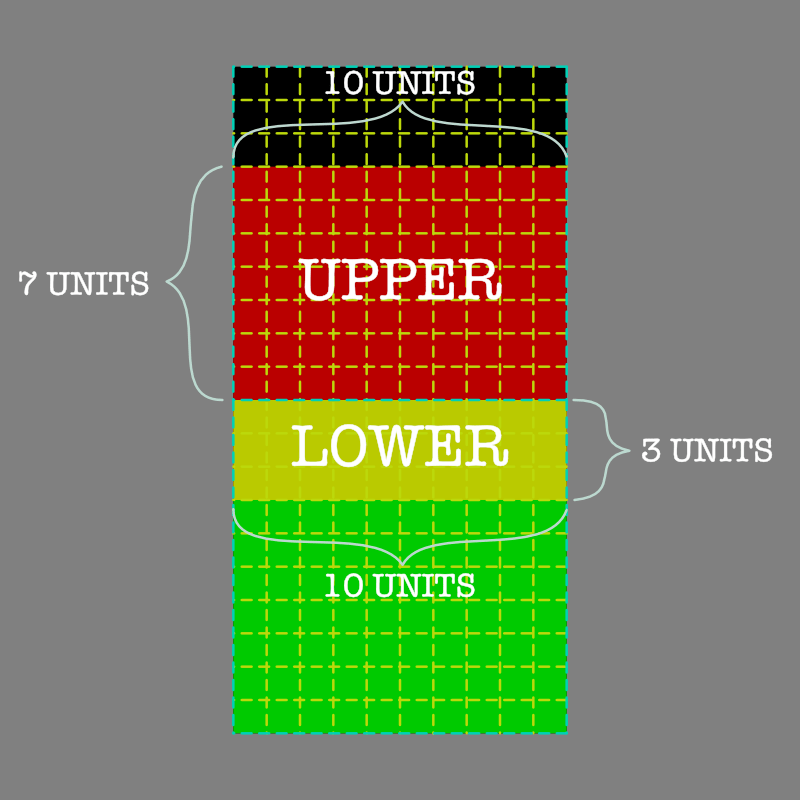

Given we are talking about two pixel windows with our example having 100 units of coverage in each, let’s see how the geometry breaks down…

We know our geometry is conveniently based on the 100 unit divisions, and we’ve moved the pixel down 30% into the destination, or three rows. We also know the emission strength of our starting red pixel of 50%. We have enough information to manually calculate the proper result for our mixing.

Our upper pixel window consists of 100 geometric units, and now our red emission of 50% total display light is only covering 70% of the remaining upper window. The result?

UPPER PIXEL: 0.70 * 0.50 = 0.35 == 35%

And our lower window? That’s a little more complex isn’t it? First we have two regions, the yellow and the green region. We are going to calculate each individually, then add them together to get a proper mixture.

First the mixed yellow portion. We can see that it is covering 30% of the pixel window where the red and green emissions overlap, and our emission was originally 50% red.

LOWER PIXEL: 0.30 * 0.50 = 0.15 == 15%

Surprise! Nothing has changed from Question #22 here! The values are exactly the same for the red pixel. What has changed? Now the red portion covers 30% of the window that is emitting 60% green underneath. To that green pixel, we need to add our small 30% portion, which is emitting the original 50% emission red.

So what’s the final pixel emission components? Let’s add the two together.

LOWER RED [0.15, 0.00, 0.00]

LOWER GREEN [0.00, 0.60, 0.00]

SUM [0.15, 0.60, 0.00]

And then we encode the values according to the particular display’s transfer function. Again, for a commodity sRGB display, that’s a pure power function of 2.2 for the output, so we inversely encode the values.

LOWER RED 0.15^(1.0/2.2) == CODE 0.42

And our green portion is encoded as the following.

LOWER GREEN 0.60^(1.0/2.2) == CODE 0.79

And our blue portion is encoded as the… ah right… it’s zero. Zero is zero when we roll it through the magical encoder.

LOWER BLUE 0.00^(1.0/2.2) == CODE 0.00

Final sRGB-like triplet?

LOWER RGB CODE [0.42, 0.79, 0.00]

And recall back that our upper pixel window has 70% of the coverage with a 50% emission red, which is as follows.

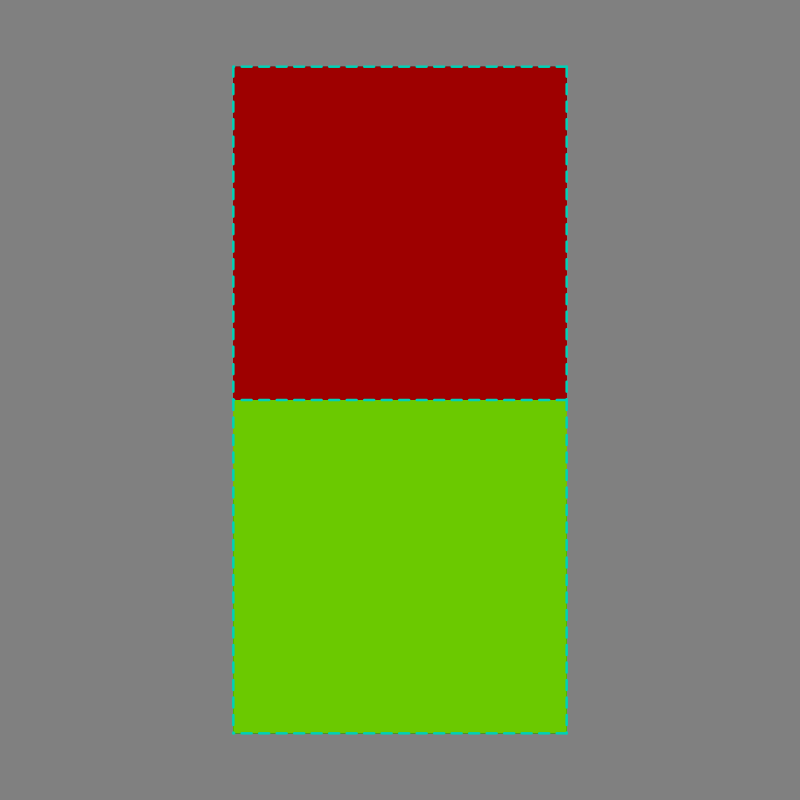

UPPER PIXEL 0.70 * 0.50 = 0.35^(1.0/2.2) = 0.62

UPPER RGB CODE [0.62, 0.00, 0.00]

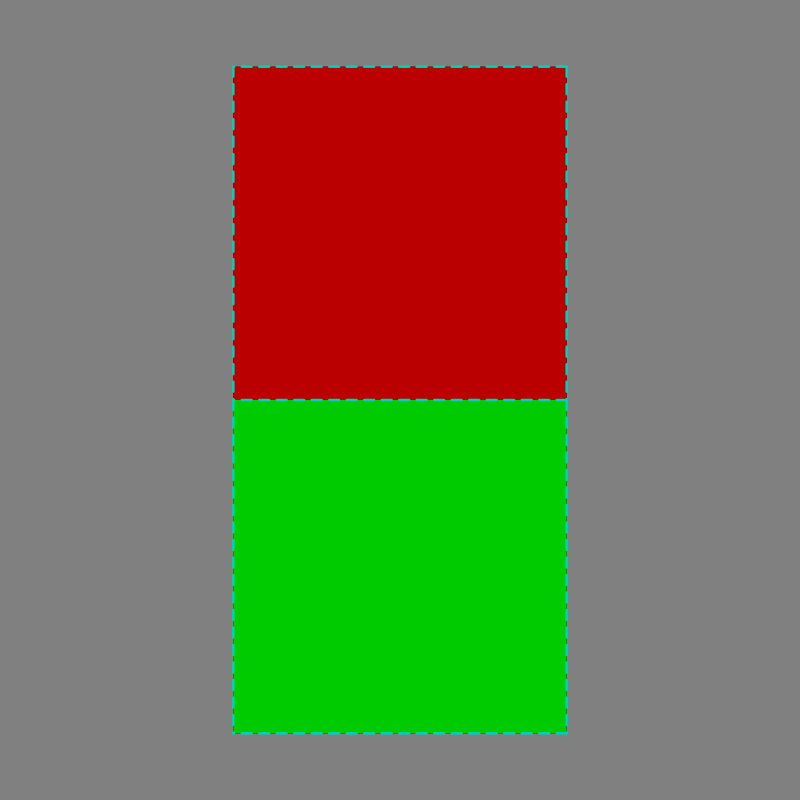

What does it look like? Glad you asked…

As slow and tedious this has been, hopefully you have seen that adding the emissions of the two pixels is extremely straightforward. It’s clear, simple math, with a clear and simple encoding to the display’s inverted transfer function. Much wow. Much simple.

Answer #23: To move one emitting pixel over another, we simply calculate the relative geometry and add or remove as required.

Our calculations are nothing more than extending the exact same ideas that started with geometry of emission in Question #20, as applied to pixel encodings in Question #21, and pixels moving geometry as in Question #22. It’s that simple.

And with that we have expanded our understanding of light mixture by building on top of the three previous questions.

You are probably wondering if this is getting darn close to that slippery subject called “alpha”, and you’d be quite right. In fact, we are now able to discuss what happens under the hood…

1 For those interested, the two titles at the top of this post are wonderful entries into the rabbit hole. It should be noted that the rabbit hole got plenty more deep, literally, with the advent of “deep pixels”. None other than Mr. Duff himself, at Pixar, has been responsible for fleshing out our conceptual models further.