Back at Question #6 we discussed the idea of an “encoding transfer characteristic”. That mouthful of marbles is worth drilling into more closely. This do-over of posts is hopefully going to finesse some details of the rough sketch presented in that earlier post. The painstaking work a restoration craftworker goes through restoring work to it’s intended form…

And of course, the obligatory question…

Question #37: What is a transfer function and is there more to this puzzle than it seems?

A Tale of Two Ideas

To help frame this discussion, let’s remove all of the bulls*it and cut to the chase of what we are presented with when we think about what an encoded signal is. To borrow from one of those baguette, cheese, and wine consuming French philosophers…

“there is no outside-text”

Jacques Derrida, from On Grammatology

That is to say that there’s nothing more to a display signal presentation encoding than a two dimensional quantification of relative energy presented to our contemporary-era-primate senses. And that energy field is a projection of some values sent to the hardware function. So let us focus on this and work backwards from the meatware sensorium, to the energy being emitted from the medium. But, sadly, there is way more to transfer functions than that of the mere presentation of stimuli…

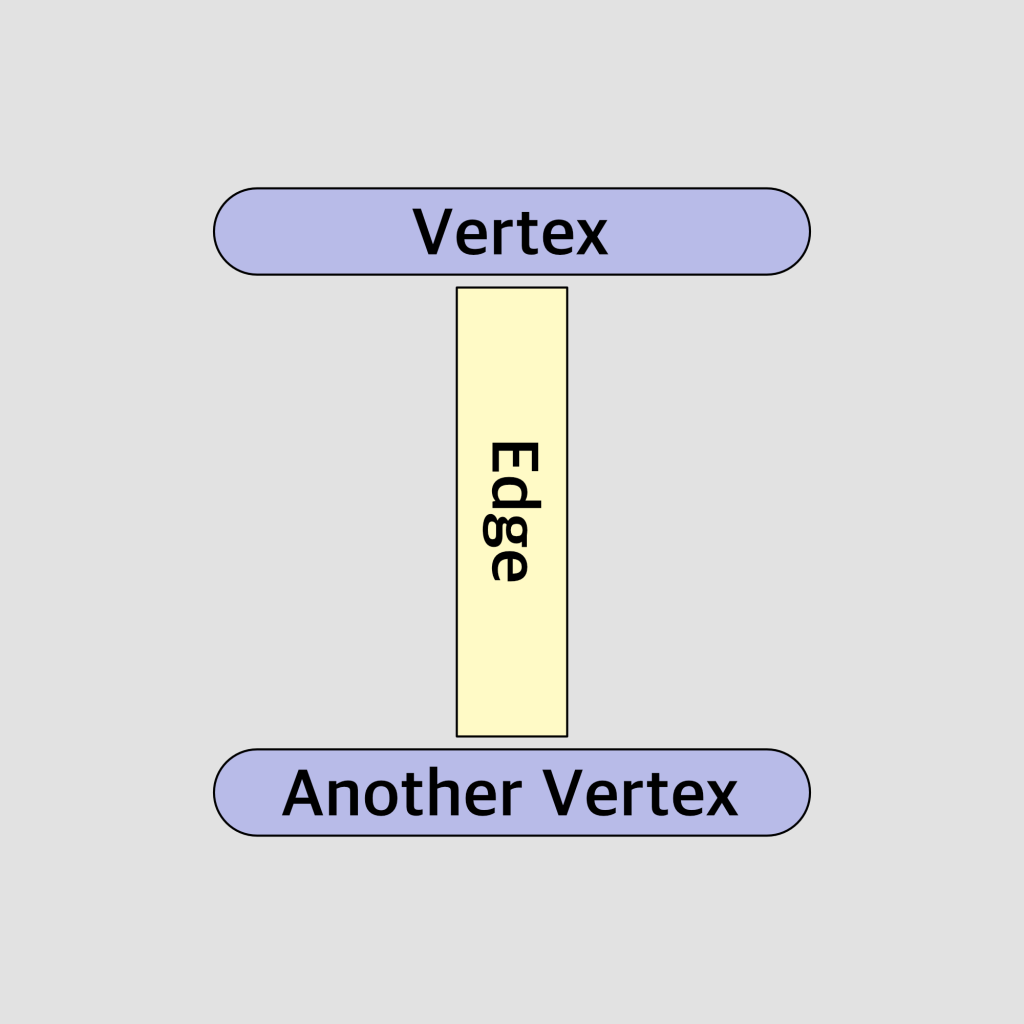

We are going to employ what is known as Graph Theory to try and describe the relationship between data states and “meaning”. Graph Theory is just a convenient way of representing things and their relationships to other things, in the form of a chart-like graph. These are often of the form of a “thing” in the graph, which is commonly called a “vertex”, and a relationship described by an “edge”. Hopefully we will all understand why we are harnessing this sort of a mental model later, as we try to cut through the reams of nonsense out in the wild of the intarwebz.

Data States and Operators

So what then determines the relative wattages in a display presentation from Question #36? What drives those tiny emitting sub-pixel attenuating or emitting regions at every spatial pixel sample? The answer is of course the encoded values. Let’s focus on two simple ideas…

- Data State.

- Operation.

Given what we’ve started to carve out regarding display mediums, and the nature of encoding transfer characteristics, this division between “state” and “operation”, we shall see, is more slippery than expected. In fact, we could go so far as to suggest that one of these ideas is subservient to the other!

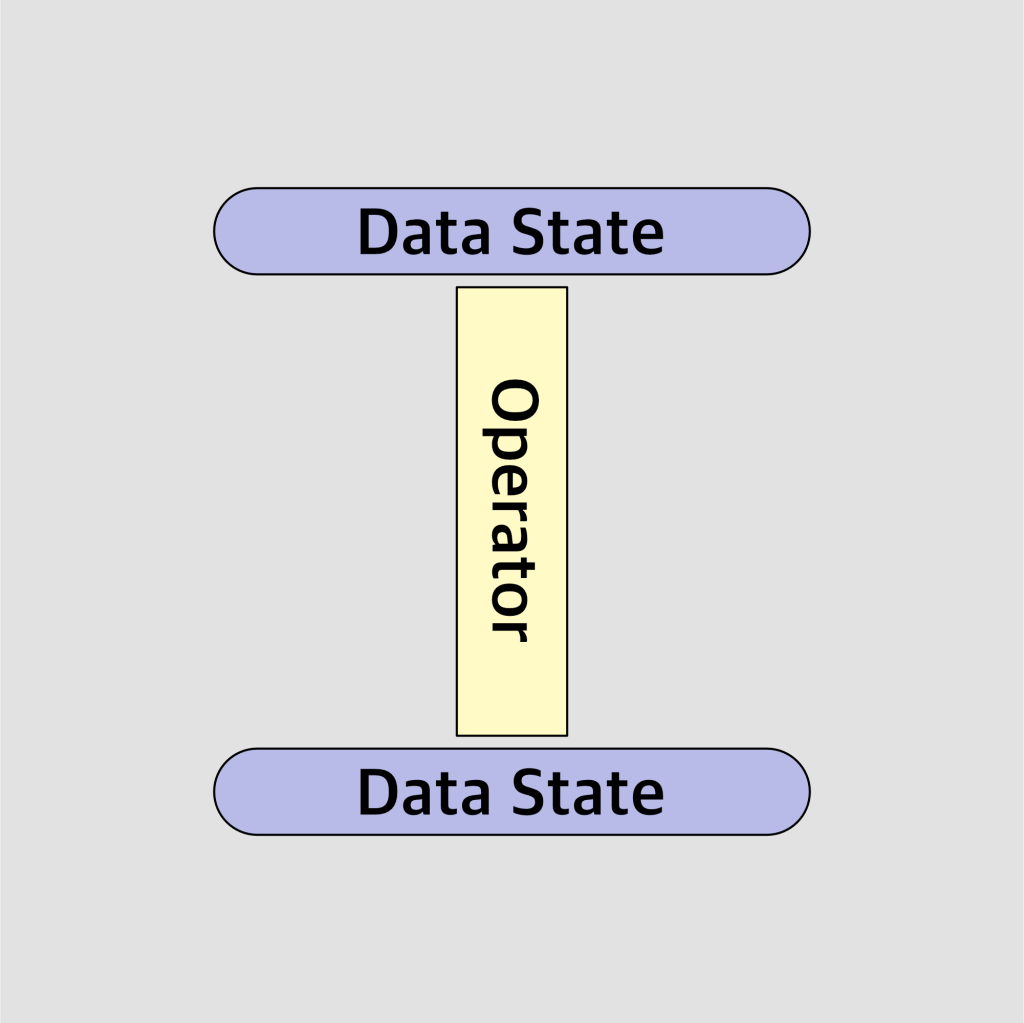

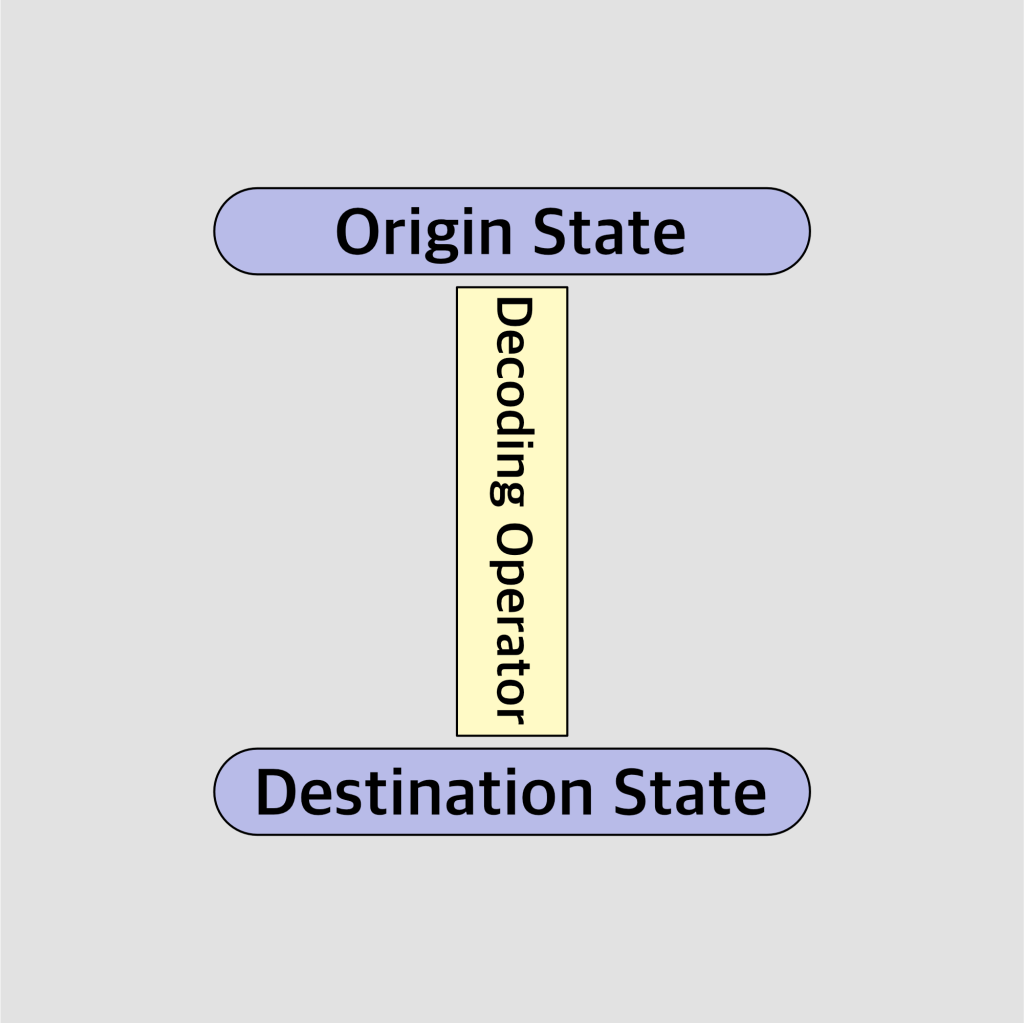

To revisit a Graph Theoretic approach, we would have something like the following diagram. Note that the edge here, which we’ve labeled as the operator, is not necessarily “directional”. That is, some operators can be “inverted”, and other operators cannot. If we can invert our function by way of a bijective mapping, we could travel either direction in the graph. If however the function is non-bijective, there’s a good chance we can only traverse in a singular direction. This is why the diagram does not use an “arrow” to imply directionality here. Let’s just keep things open ended, no pun intended.

Data State

When we decide we are going to stow some “information” into a signal, we have to have a reasonable idea of some formal “meaning” of what it is that we are attempting to encode. As hopefully outlined prior, when discussing presentation decoding, the actual code values we discussed way back at Question #6, and elaborated in Question #36, are actually relative wattages in a uniquely encoded parcel. Encoded is a great term, as the term implies some sort of “decrypting” operator to decode them. Assuming we have asserted that we know what we are doing, we can hand craft an encoding function. But what function should we use?

This question is the tip of a much larger iceberg for anyone who reads the comments over at Reddit when discussing BT.709 versus BT.1886, or the often ahistorical discussions of the IEC 61966-2-1 sRGB versus 2.2 power function encodings and decodings. It’s about as treacherous a territory as possible, so hopefully we can do a little bit of work to instil an intuitive sense of what is going on that someone can carry forward with them.

As folks know, we can only assert so much as an encoder. Once we stuff our bits into the shipping box, and hand it off to the delivery corporation, we can never assert that the receiver gets the parcel as we intended it to arrive. If we think about an encoding of a word such as Envelope, we can quickly see that despite a specific intention in the encoding, the decoding is fundamentally ambiguous. Which leads us to a second ontological demarcation, but first, let us update our diagram.

Operation

It should be noted that in the process of packaging our intended meaning into the RGB triplets, the action of packaging involves the aforementioned operator; we apply some sort of function to our input. In dorky math terms, it might look something like:

encoded_value = function(intended_meaning)

At this point, we should see something sort of hidden in plain sight; our function is completely oblivious to whatever meaning metric we are feeding it. That is, it is up to us, the meatware primate, to make sure that whatever we pass to our encoding characteristic function encompasses the intended meaning we wanted.

The function here operates as a meat grinding sausage machine. If Uncle Richard, instead of the beef slab, happens to accidentally poke his finger into the grinder, the grinder cares not, and will simply stuff the sausage with whatever substance it is provided, even if Uncle Richard’s digits were not necessarily the intention! That is to say that the intention is always subservient to the operation.

Looping back to decoding transfer functions, if we encode the code values dumped byte by byte out of an MP3 file, it doesn’t matter! At the point we are pushing the MP3 code values through our operation, the operation is the thing that drives the meaning, and now those MP3 code values could be considered “encoded as relative wattages” if we happen to be using the “operator” of a BT.1886 display.

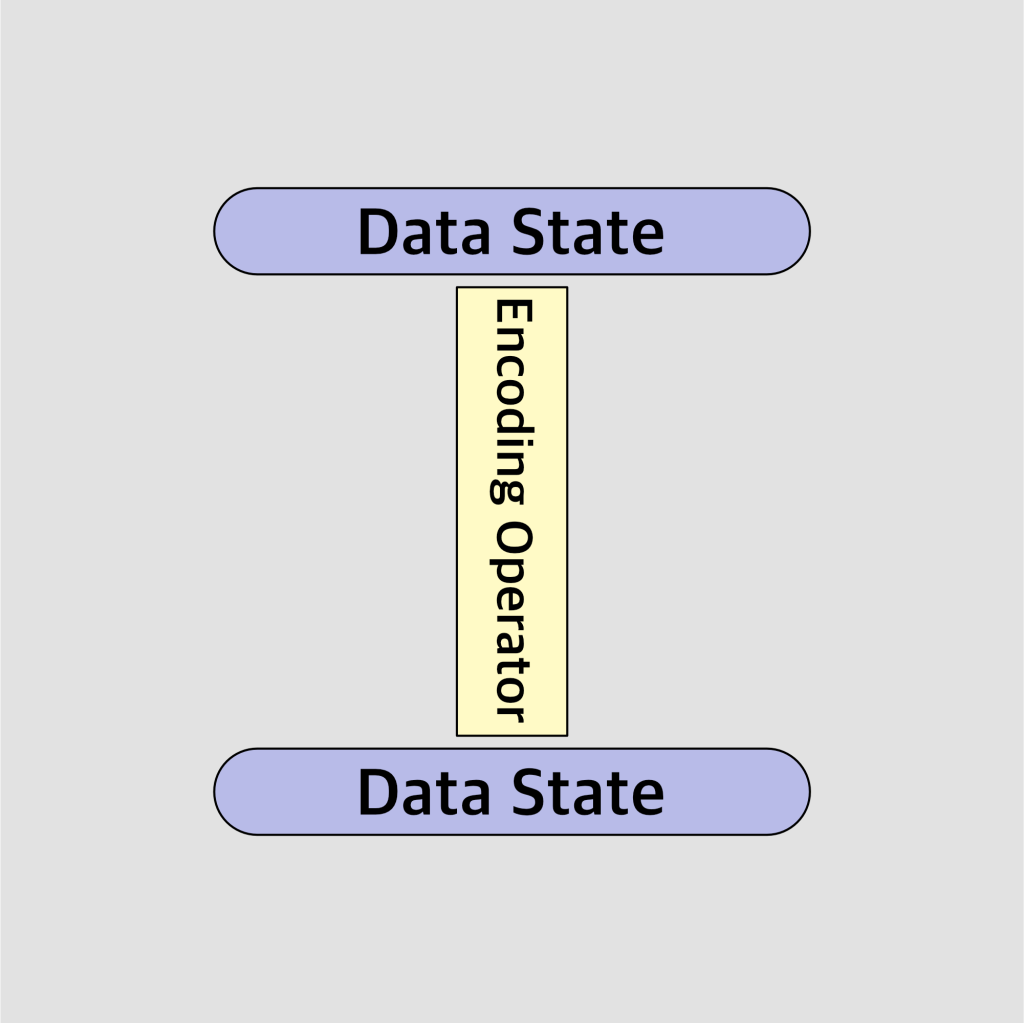

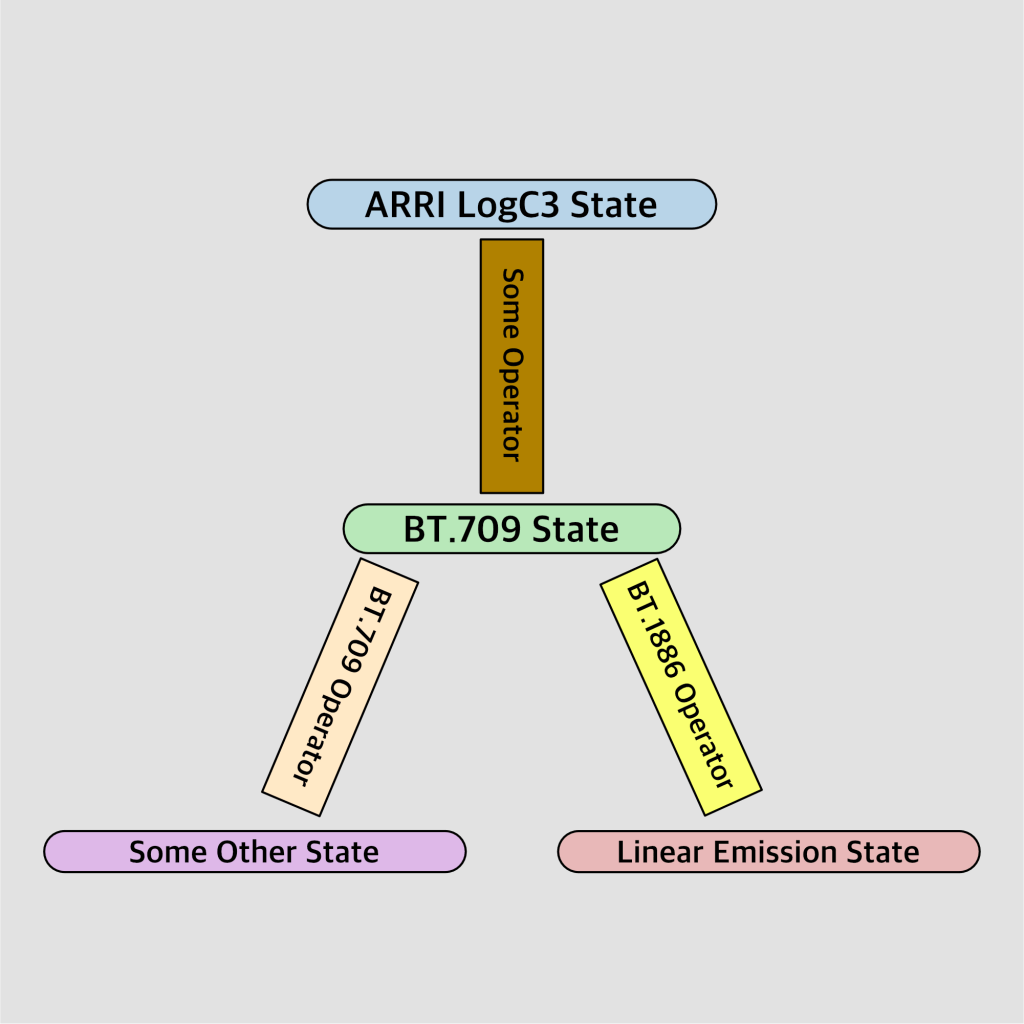

So why fixate on this point? First, let’s update our diagram to include the idea that the operator drives our state.

Operators Govern All

When we think about what is presented before us in a pictorial depiction, we need to focus on the operation at hand in the hardware of the display. What happens if the encoding meatware primate explicitly encoded the digital signal for a Foo display, and another decoding meatware primate happens to arbitrarily send the encoded values to a Bar display decoder? That’s right… as we learned above, everything is subservient to the operator! Just as Uncle Richard’s digit may not have been Uncle Richard’s intended meat content of the sausage, the operation of the sausage machine cares not.

In much the same way, our operator here drives the meaning; the meaning becomes the operator’s output explicitly. The resulting state is always relative to the operator’s machinations at that specific moment.

Feed Alexa LogCv3 normalized code values directly to an sRGB power 2.2 display? Guess what? Those code values become power 2.2 decoded emissions! Feed normalized AdobeRGB code values directly to a Display P3 MacBook Pro? Presto… instant Display P3 emissions! Apply the BT.1886 operator to BT.709 encoded values? Presto… the operator has forced those values to be decoded as BT.1886 power 2.4 decoded emission levels!

Let’s update our diagram…

From Operator to Emission

Having focused a bit on different operators, it should become apparent that any given data state doesn’t carry an implicit “meaning”, but rather that the meaning is driven by the chosen operator. Hopefully this is an intentional meaning, but as we have seen with various things related to managing stimuli in our electrical era, not all always goes well.

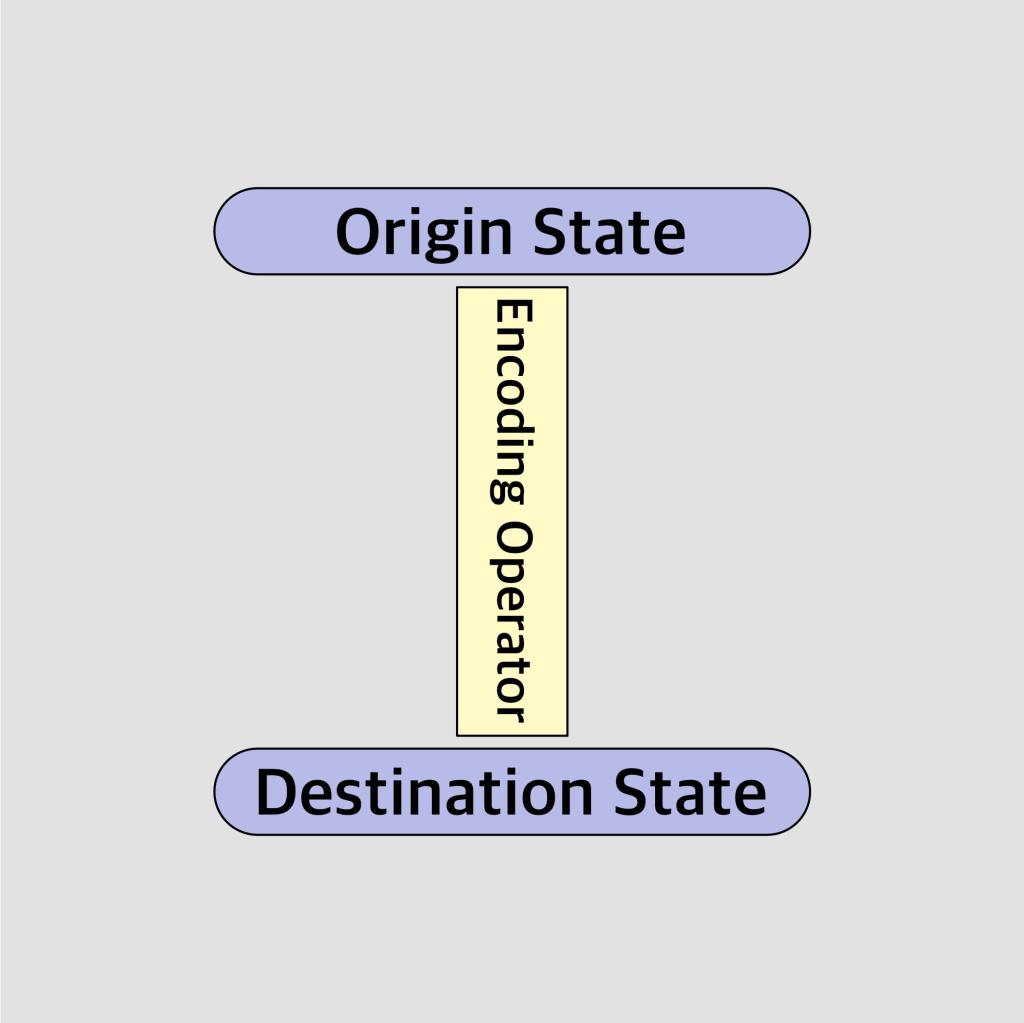

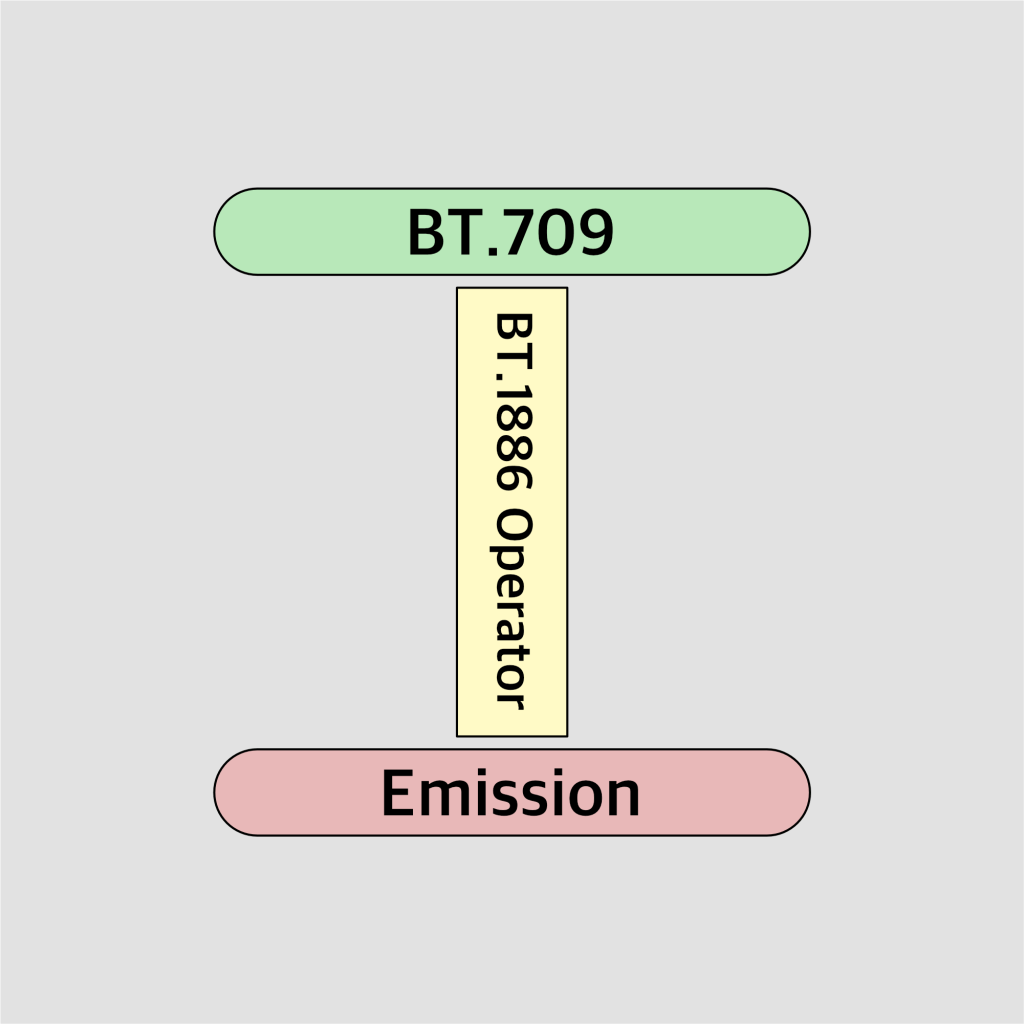

There’s a seismic realization here, and it is perhaps most elegantly presented by our Graph Theoretic mindset. But before we go there, let’s outline a pretty common case, which is where an encoded state and encoding operator differs from the decoding operator. That case is the infamous BT.709 to BT.1886 chain. You know, the one that is implied every time we crack open YouTube, or a Steaming Turd Service, etc.

Note that all that matters in this diagram is the outgoing emission. The encoding origin state is subservient to the way we treat it via the operator, which in this case, is the BT.1886 decoding function. The rest is absolutely irrelevant.

This leads us to a potential theoretical exercise which is to ask ourselves whether or not the encoded state “meaning” survives this operator. In the case of BT.709, which is the backbone of a vast array of motion picture services and presentations, we care not how the encoding was generated. Arri LogC3 with something done to it, Sony SLog2 with some random curve applied, or some random processing of a Fuji FLog… none of those data states mean much of anything. The mighty hammer of the decoding operator creates the meaning, which in the case of a display transfer function, decodes the values to display emission relative wattages. Remember this the next time someone says “This is the log encoding” and shows you a picture… it’s not “log”, because the display created the meaning of the values by way of it’s operator. The presentation is just radiometrically linear stimuli because that is what the BT.1886 display operator treats the code values as.

One Data State, Many Meanings

Let us now realize the implications of what has been outlined above with a question. How many meanings are present in a given data state?

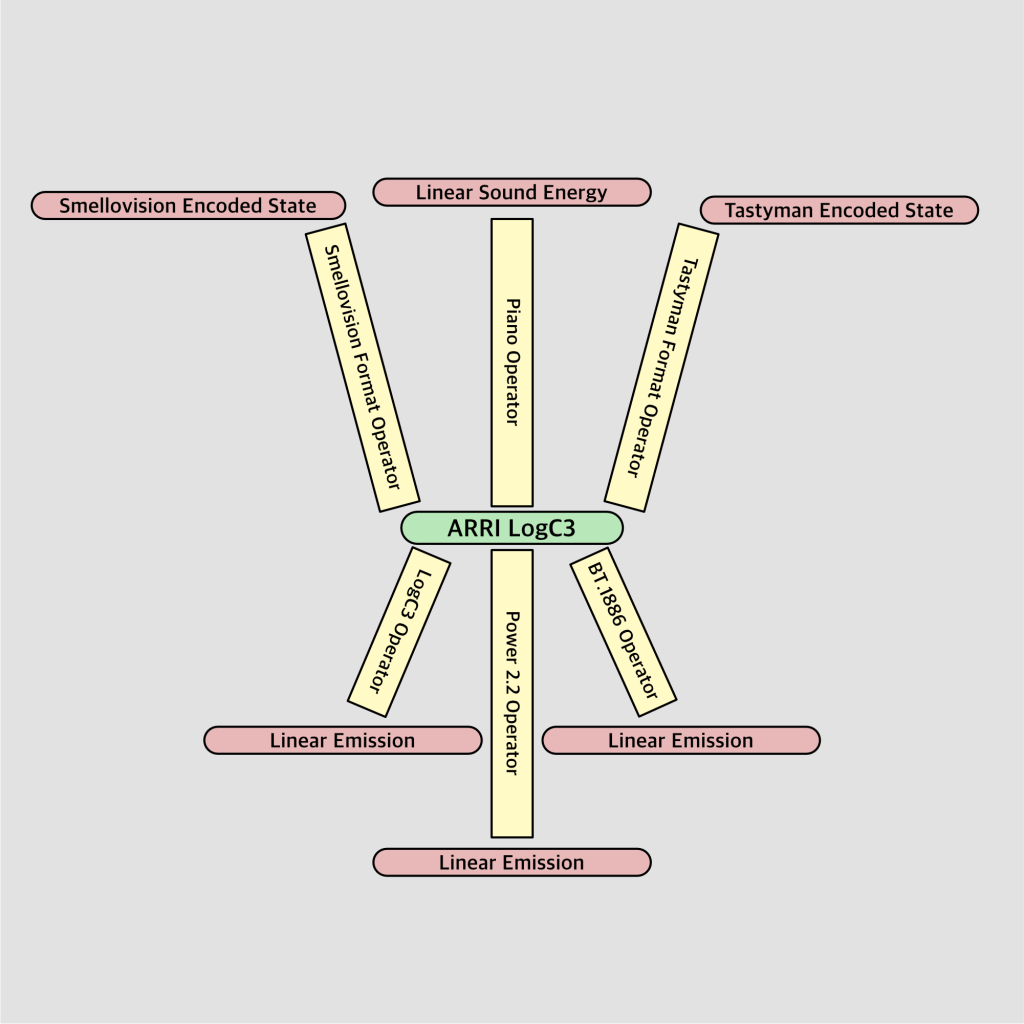

Hopefully the readers of this pile of gobslop will have realized at this point the answer must be “infinite”. The question can ultimately be framed as “intentionality” oriented, but for now, we can stick to our Graph Theoretic diagram and consider the meaning firmly anchored in a chosen operator.

Note that there’s some distinction in the domains spanned by the “Linear Emission” state in the diagram, but hopefully it is broad enough to make a case that there should not be some sort of implicit assumption as to the veridical “meaning” of a state. We can employ said state to whatever our primate whims happen to be.

That fruity diagram, if we take it back to the basics of the idea of multiple states, could be realized in the absolute confusion over BT.709 encodings; the confusion arises due to the lack of an awareness of the multiple operators that are applied to the BT.709 encoding, from a loosely defined specific entry point camera.

The Takeaway

The takeaway here with what is hopefully a useful romp into a graph presentation of transfer functions is that folks should not permit bumbleforeskins confuse them into believing some other nonsense about mythical “scenes”, “displays”, or the bogeyman of “linear”1. The “meaning” of a given state is driven solely by the operator function we choose to apply to it.

To really punch this idea home, think about all of the contortions and gesticulations that colourimetric transforms place upon the quantal catches of an Arri Alexa data state parcel, which commonly ends up “Arri Wide Gamut” in an “Arri LogC” transfer function of some sort, camera version depending. In terms of colourimetric definitions of the stimuli, what percentage of discretized pixel samples in the presented picture stimuli do we think ends up “the same as” those colourimetric definitions that were encoded?

Would it surprise anyone if they were told that the answer was effectively zero? That’s right, in terms of the presented stimuli‘s relationship with the stimuli that was in front of the camera, as expressed using colourimetric coordinates, the total pixel samples that are “the same as”, for all intents and purposes, is zero.

In plain language, none of the stimuli that was present in front of the camera ever ends up presented to the audience in the default Arri chain that has driven the vast bulk of movie making over the past couple of decades! And we are not talking about “preferential minor tweaks”, but something far more peculiar.

Answer #37: A transfer function is “just another function” that takes some input, and outputs something relevant to the function in question. There’s no veridical “meaningfulness” to a given state, and instead, the operator must be considered relative to intended use.

This post purposefully avoided the confusing terms and ideas of Electrical-Optical Transfer Functions, Optical-Electrical Transfer Functions, and all the rest of the mess. The reason is that it is important to step back and understand that some overarching and grandiose veridicality of meaning for a given state does not exist, and is rather a result of what operator we are choosing at any given moment. There will likely be another post in this transfer function series to hone in on some other tidbits.

This statement of multiple interpretations of a given data state is not intended to undermine folks who are seeking some degree of meaning for some specific process. Proper attention to the operators at a given point is of course the only way to ensure an authorial intended decoding on a BT.1886 display etc. It is important that we assert that the proper operator is being applied to the data state for the intended purpose.

For example, a rendering person might want to know some sort of proportionate signal response to emulate what a modelled display screen in their renderer would emit as a texture, in relative energy terms. What then is the correct operator here? Would it be the BT.709 transfer characteristic, inversely decoded? Would it be the BT.1886 transfer characteristic applied to the encoded values? Or would it perhaps be the inverse of the Arri transfer characteristic which played a role in the pictorial depiction? Which one is correct??? We shall leave the answer to the readership, who it is with great confidence will deduce the proper operator.

There are likely a good number of readers who were baffled by the final assertion made that approximately none of the colourimetrically derived stimuli values survive to the pictorial depiction from a camera. Perhaps some might scream “Hogwash!”. Some might suggest “That’s a bug!”. We can almost hear them shrieking about “scenes” and “displays” and other horsesh*t. The claim is made specifically for those minds, and is not at all an accident.

The perplexing nature of the proposition around cameras and what they do may have cascading implications such as pondering what then is presented if not the stimuli-equivalents that were in front of the camera? What do these camera devices do if not to aspire to present the stimuli that was in front of the camera as accurately as possible? What the heck is presented then? What is all of this rubbish burger about camera colour accuracy and what not propagated by camera vendors and some factions around pictures?

As you likely have noticed, we are swirling around similar topics over the past few posts. Sadly, the utterly confounding nature of those questions, and perhaps some insight as to more robust frameworks of understanding, will need to just wait…

- At this point, again, most bumbleforeskins can be disregarded when they say “linear”. Often times they are caught in the confused exhaust fumes of a 1970 Volkswagen Beetle as they fail to acknowledge the many potential operators that could be applied to a given data state. When pressed, you’ll quickly realize that it isn’t their lips that are moving, but more often than not, the noises are coming from their hind hole. The one most significant and important thing to always remember is that the human visual system can only parse one specific thing with regard to primary input, and that is radiometric energy. And newsflash… Radiometric energy is always “linear”. As such, the entire term “linear” ought to be met with the skeptical force of a thousand suns when someone presents it. ↩︎

One reply on “Question #37: What the F*ck is a Transfer Function, Again?”

The series has been very engaging, thank you for writing all of this. Awaiting eagerly the 38th eye opener.

LikeLike